AC Milan’s Champions League adventure is over, but their 2-1 away win at St. James’ Park this week managed to secure Europa League football in the New Year. Below is the tactical analysis of the performance.

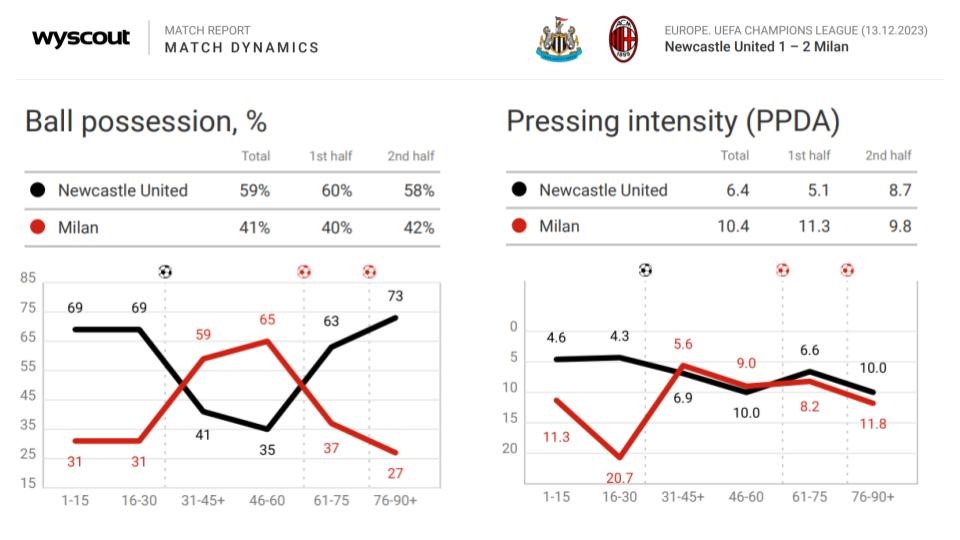

The Rossoneri needed to come from behind to win, with Newcastle taking the lead in the 33rd minute. The home team were much the better side in the opening forty-five minutes, dominating possession (60%) and leading the shot count 8-1.

The half-time break seemed to favour Milan, however, with the visiting team gaining a foothold in the game after the interval. Milan levelled proceedings in the 59th minute, when Christian Pulisic converted from close range at the second phase of a corner kick.

The game became stretched from here on, with either side being denied opportunities to go ahead. First, Mike Maignan’s wonder save prevented Newcastle from retaking the lead in the 69th minute and then Rafael Leão could only hit the post when presented with a golden 1v1 opportunity against Martin Dúbravka in the 79th.

In the final ten minutes, both teams pushed for a winner. And in the 84th minute, Milan countered to devastating effect to score the goal which preserved their European journey for this season.

In a cliché game of two halves, here’s @Tactics_Tweets observations of a bittersweet victory.

Set-ups & gameplans

Team-wise, Stefano Pioli welcomed Rafael Leão back into his starting eleven to slot into the left side of the Milan attack, with Christian Pulisic switching to the right to replace the outgoing Samuel Chukwueze.

From a gameplan perspective, Milan’s in-possession strategy in the first half appeared muddled. Some early long balls forward from their backline implied an attempt to deny Newcastle opportunities to press. But it only resulted in an inability to retain the ball – Milan had 31% possession in the opening thirty minutes.

Milan’s two most notable tendencies in attacking phases were 1) their full-backs pushing infield to narrow the Newcastle midfield line and create passing lanes to their wide attackers, and 2) balls into a dropping Giroud to link with oncoming runners. However, as the one solitary shot by the half-time whistle would suggest, this approach did not prove fruitful. A change in approach in the second half was needed and made. More on this later.

In defensive phases, Milan operated in their most typical out-of-possession system – man-orientated in central midfield, allowing an underload in their forward line (three Milan forwards vs Newcastle back four) to maintain an overload in their backline (Milan back four vs Newcastle three forwards). Newcastle caused Milan’s pressing/marking scheme issues in the first half, as we’ll cover next.

For the home team, Eddie Howe made his first personnel change for six matches with Callum Wilson replacing Alexander Isak. Newcastle looked to be aggressive without the ball, engaging Milan collectively from their trademark 4-5-1 formation.

In possession, Newcastle looked to use coordinated patterns of play and specific principles to manipulate (and then exploit) Milan’s defensive system – to great success in the first half. In the second half, Newcastle’s share of possession and off-ball intensity decreased, resulting in a lack of genuine attacking threat – and no attempts on goal past the seventy-minute mark.

First-half issues

All teams, especially at this level, will do extrinsic opposition analysis to help with their pre-match preparations and game plans. However, nothing beats first-hand experience. And when facing an opponent for a second time, like in a reverse fixture in relatively quick succession, you will likely have a better idea of ways to exploit the opposition’s weaknesses.

In this case study, Newcastle appeared to have a set of attacking tactics and principles to manipulate Milan’s out-of-possession system and pressing schemes – the aforementioned approach of being man-orientated in central midfield, allowing an initial underload in their forward line, and having a specific player jumps when pressing.

Here’s a variety of examples to showcase these in practice, including the multiple issues it caused Milan.

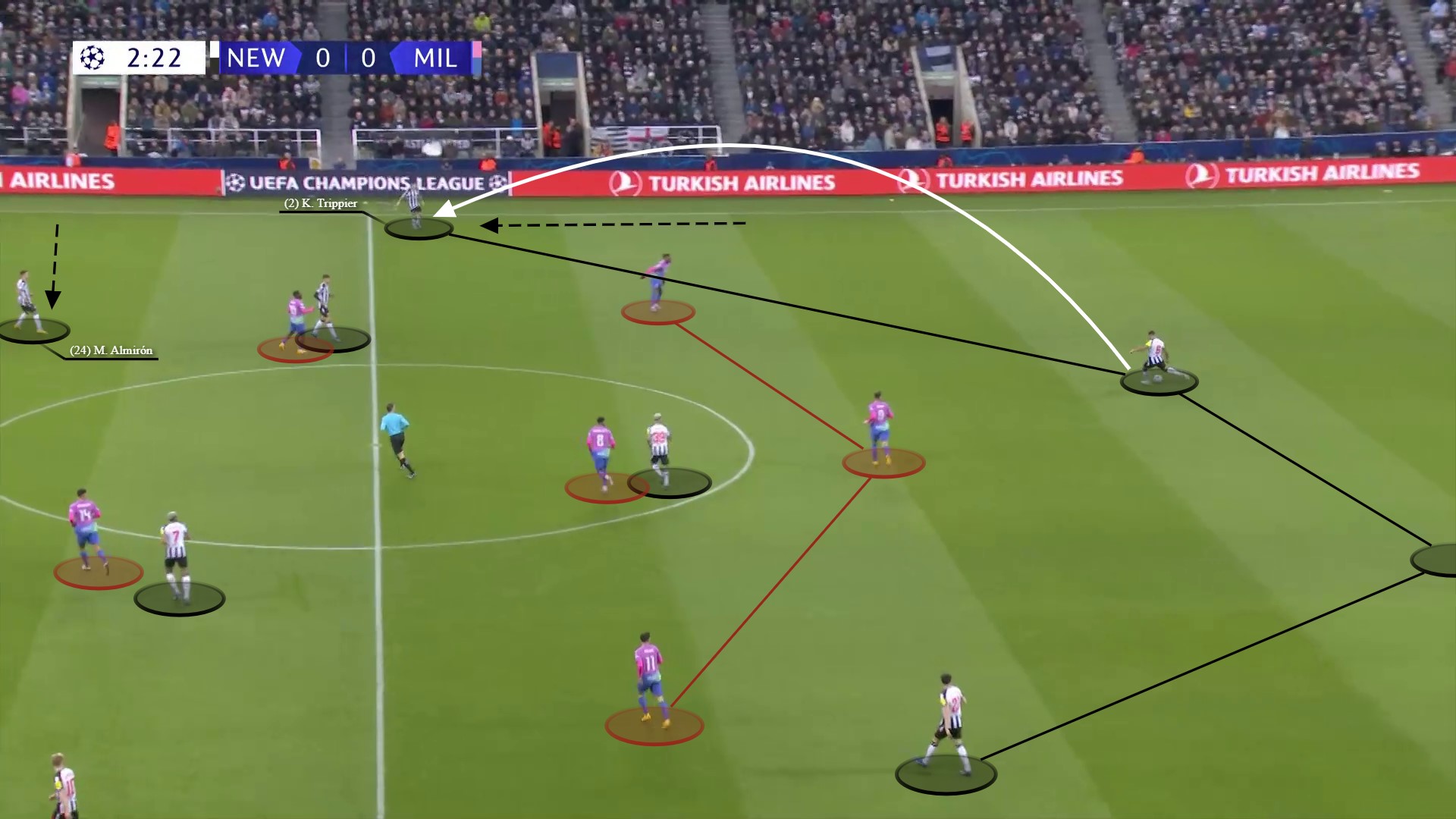

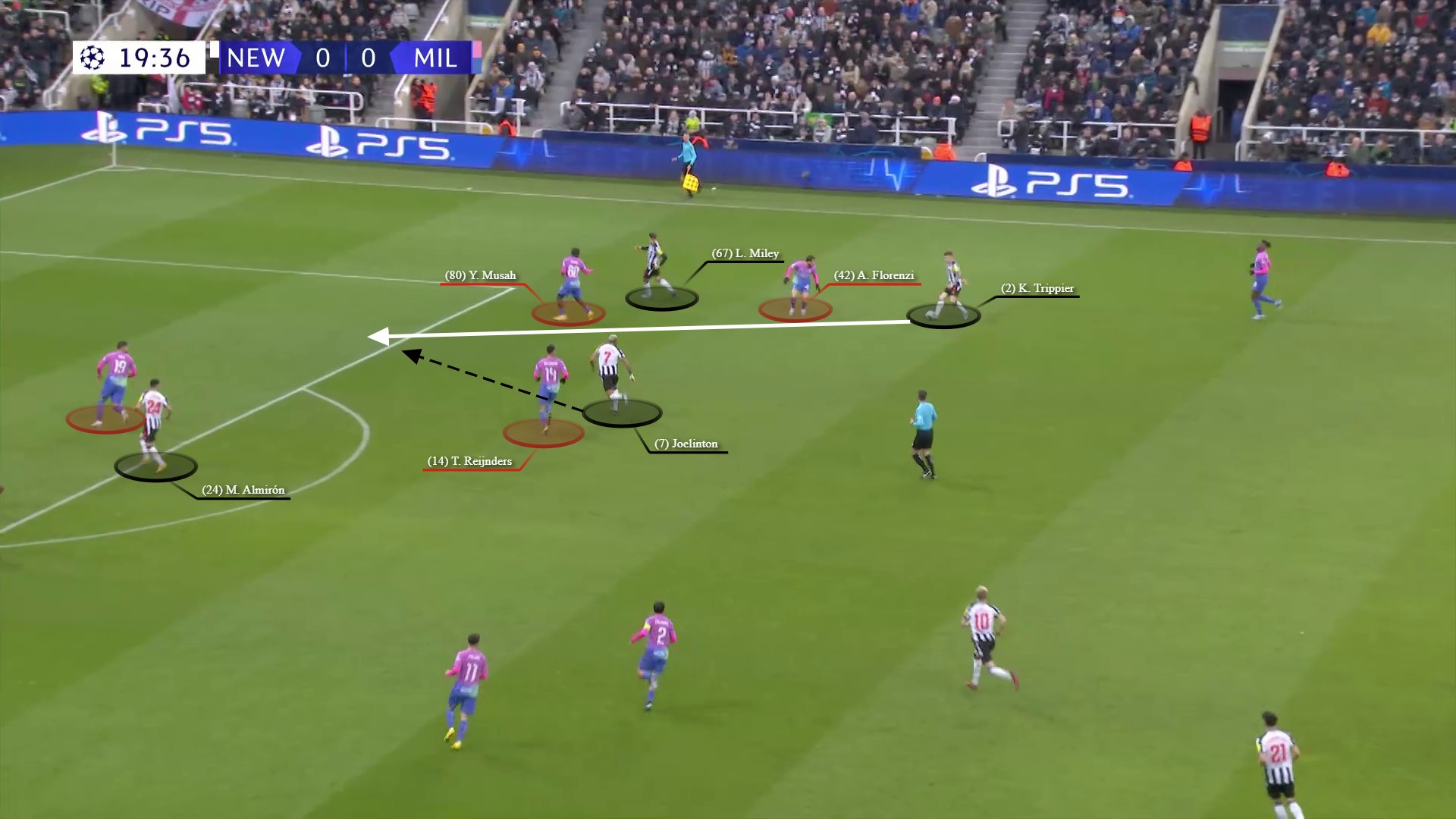

One of Newcastle’s more frequent tactics became evident within the opening minutes. The home team utilised their numerical advantage in the backline – plus, Leão’s equally lesser defensive qualities and instruction to occasionally ‘cheat’ i.e. don’t always track back, sometimes stay high so better positioned to attack spaces in transitions – to access Trippier in space on the right wing.

Ordinarily, one of Milan’s solutions to their forward line underload is for the ball-side full-back to jump to engage the free opposition full-back once they receive the ball – it would be used in situations exactly like this one. However, knowing this, Newcastle looked to instruct their wide attacker, Almirón in this scenario, to push infield to give the left-back (Florenzi) a decision to make – stay or go.

In this instance, Florenzi opted to stay. So with Almirón’s infield positioning helping pin the Milan left-back, the diagonal switch to Trippier was on and executed.

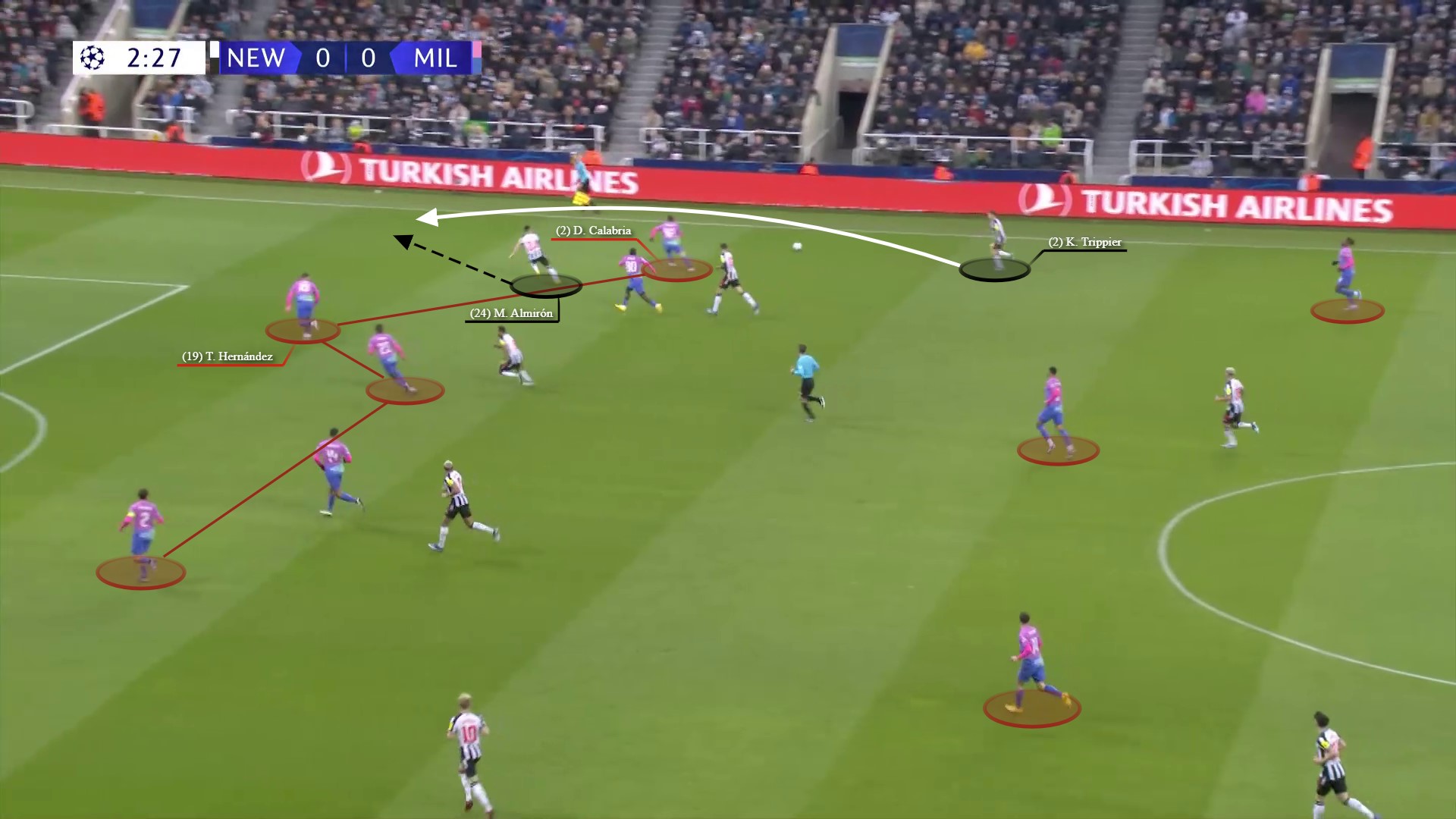

Now, with time and space afforded to him, Trippier carried forward which eventually forced Florenzi (incorrectly labelled as Calabria in the image below) to engage. Almirón exploited this new gap in the Milan backline (aided by his initial starting position) to make a run in behind which Trippier easily found. This sequence ended with a cross into the box which Tomori swung at and miskicked forcing Maignan to catch the ball as it looped towards their own goal.

A couple minutes later, another attacking principle revealed itself – this time, manipulating Milan’s player-orientated approach in central midfield. In defensive phases, Milan’s three midfielders (Loftus-Cheek, Reijnders and Musah) each cover a specific midfield opponent. The intent, make passing through the central areas of the pitch a riskier approach for the opposition with all of their midfielders closely covered.

However, whilst the Milan midfielders are supposed to become more zonally focussed as the opposition progress into the final third, like any ‘man-marking’ tactic, players can be pulled in different directions. This has the dual benefit for the attacking team of creating space elsewhere and forcing those, now out-of-position markers, large distances to recover to get back into shape.

(For reference, the Milan midfielders will still aim to stay in close proximity to a nearby opposition midfielder – but maintaining the team’s low block structure and protecting central areas in front of their penalty area is the higher priority).

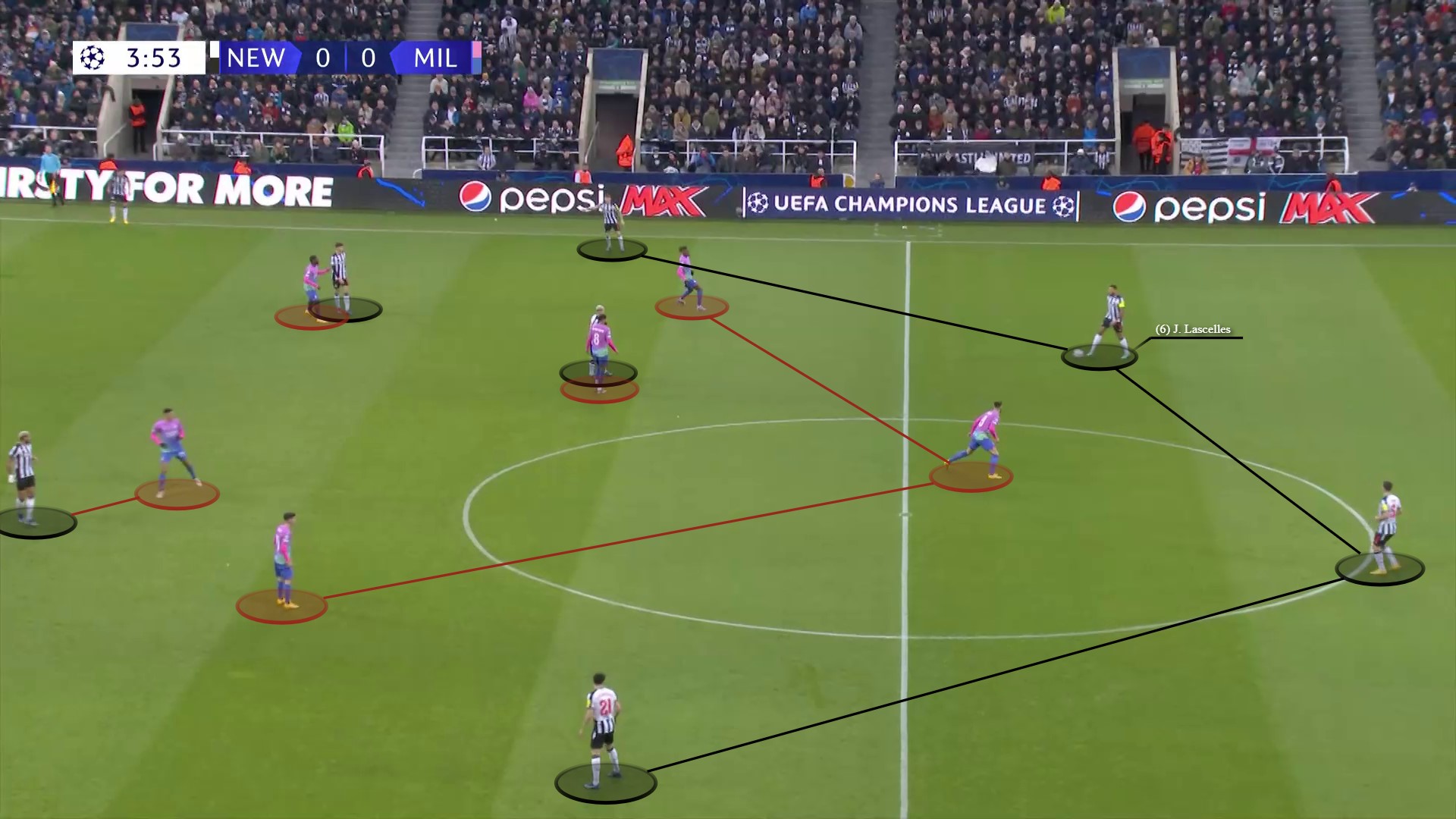

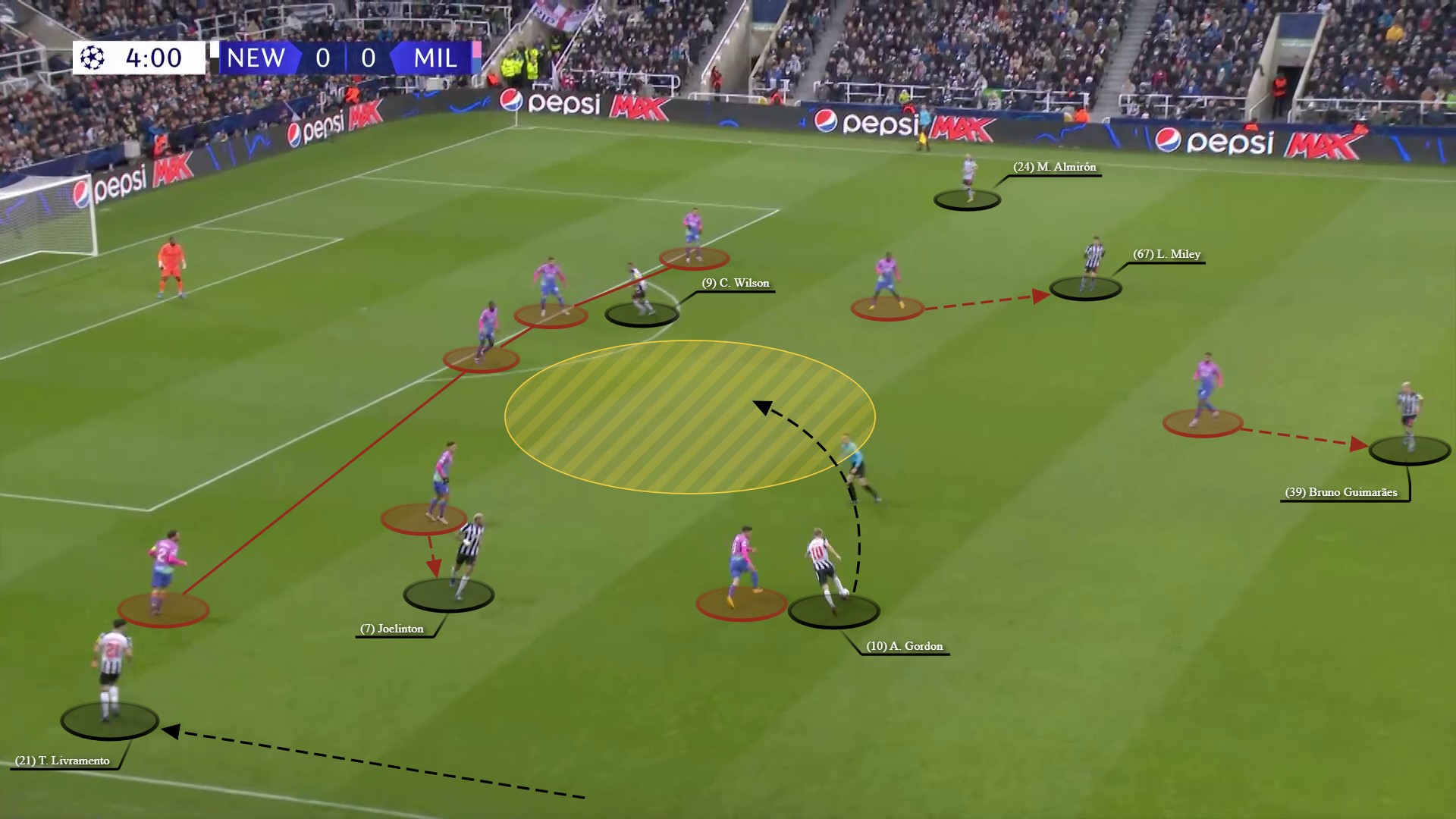

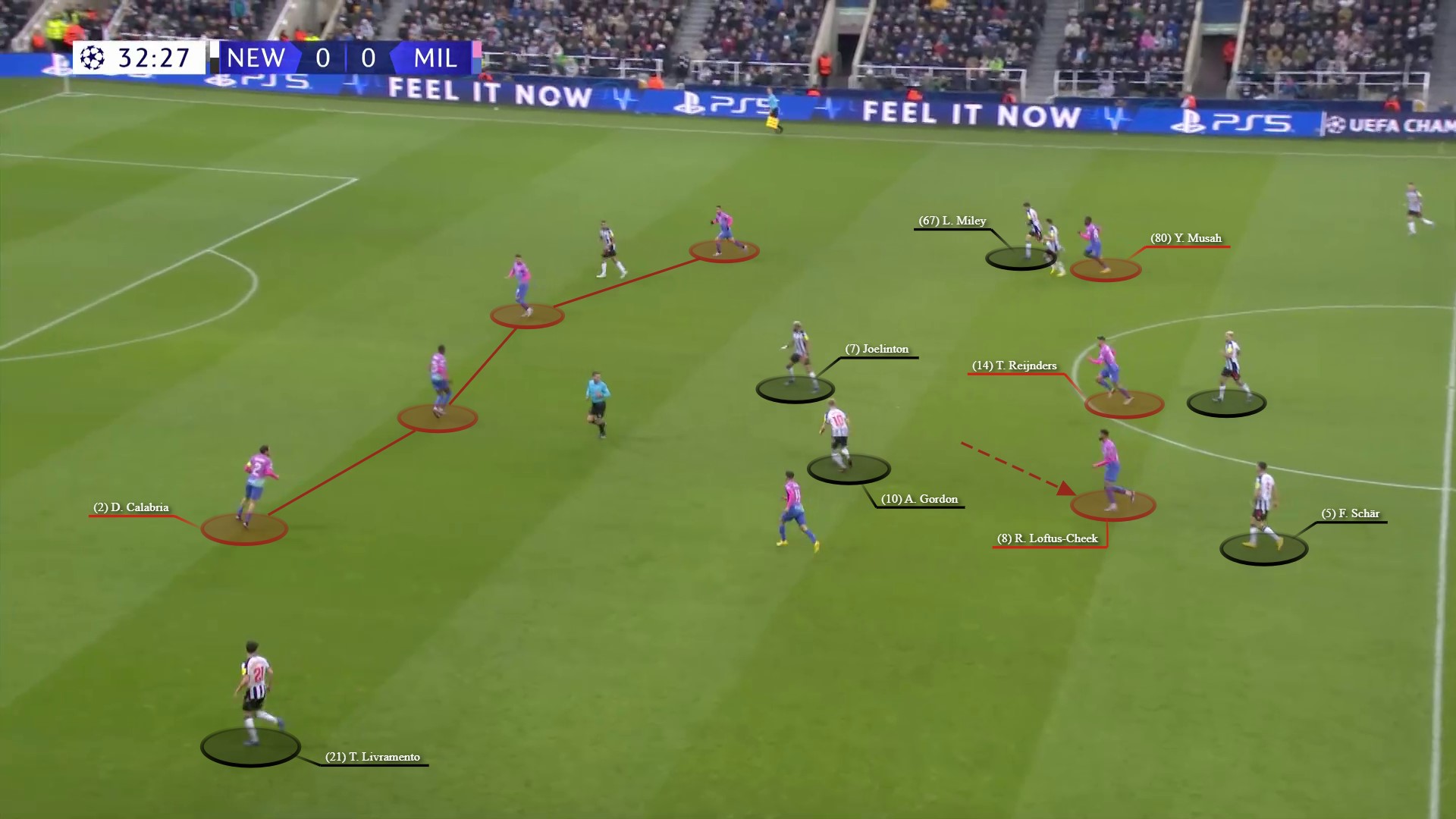

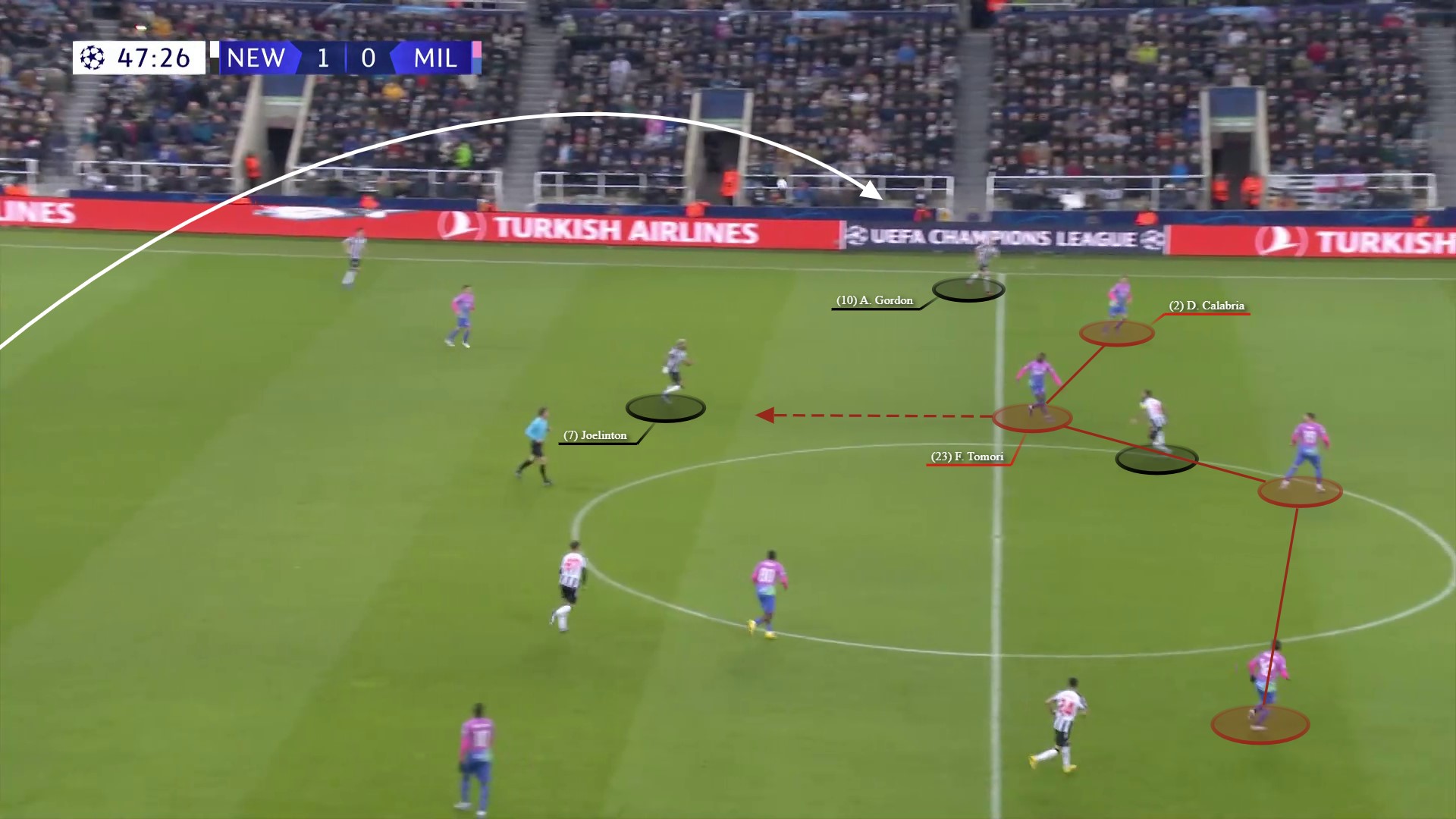

All of the above manifested itself in the 4th minute, when Newcastle had settled possession in front of the Milan block – again, see their forward line (red line) underload versus the Newcastle backline (black line) and man-orientated in central midfield (red & black circles). Here, Lascelles played a diagonal switch to the left wing towards…

…Gordon, who after controlling was able to carry infield and attack the space the Newcastle midfielders had helped create by manipulating their designated opponent. The threat of this attack forced Pulisic (who had swapped marking responsibilities with Calabria as a result of Livramento’s overlapping run) to concede a free-kick.

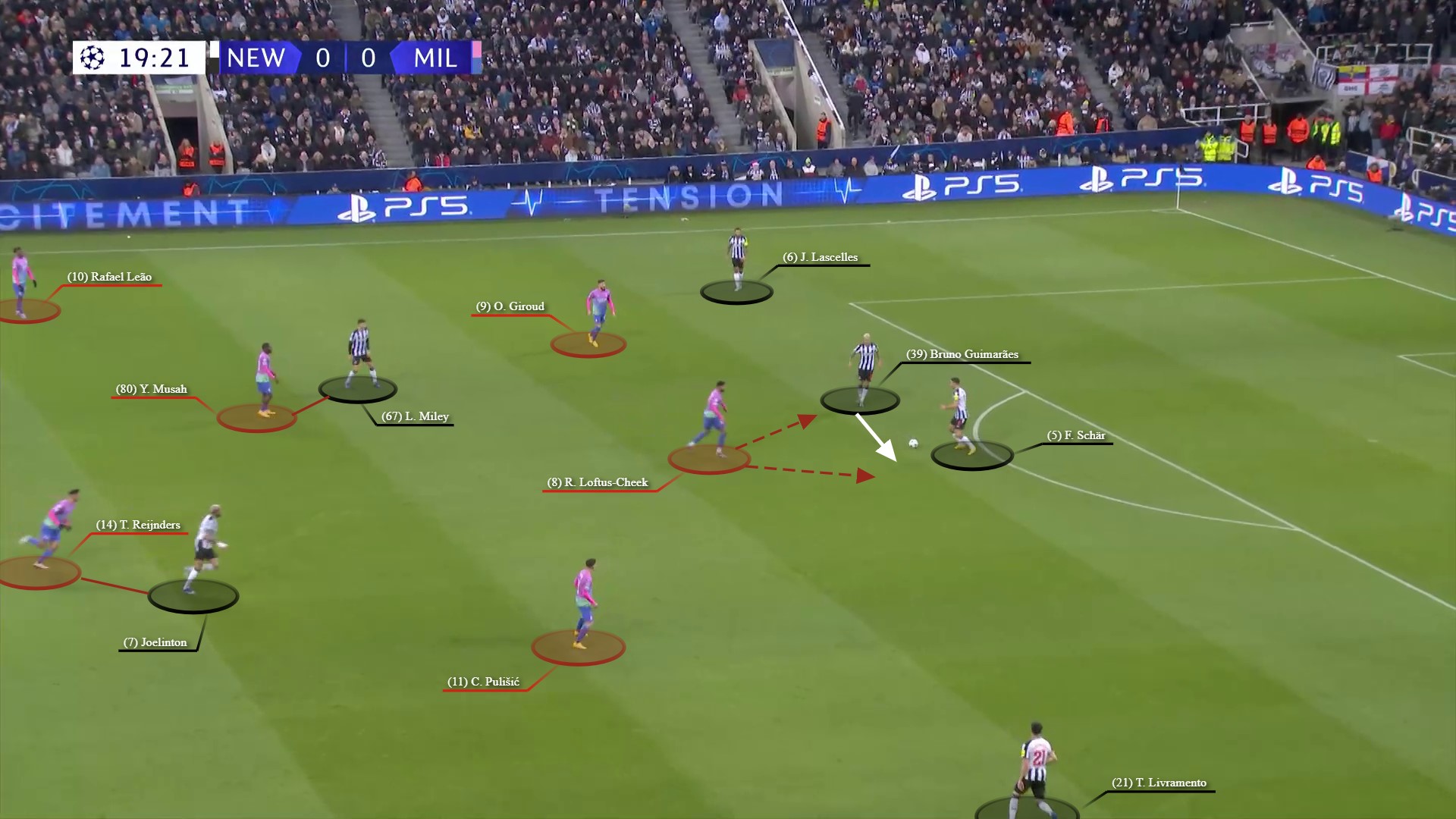

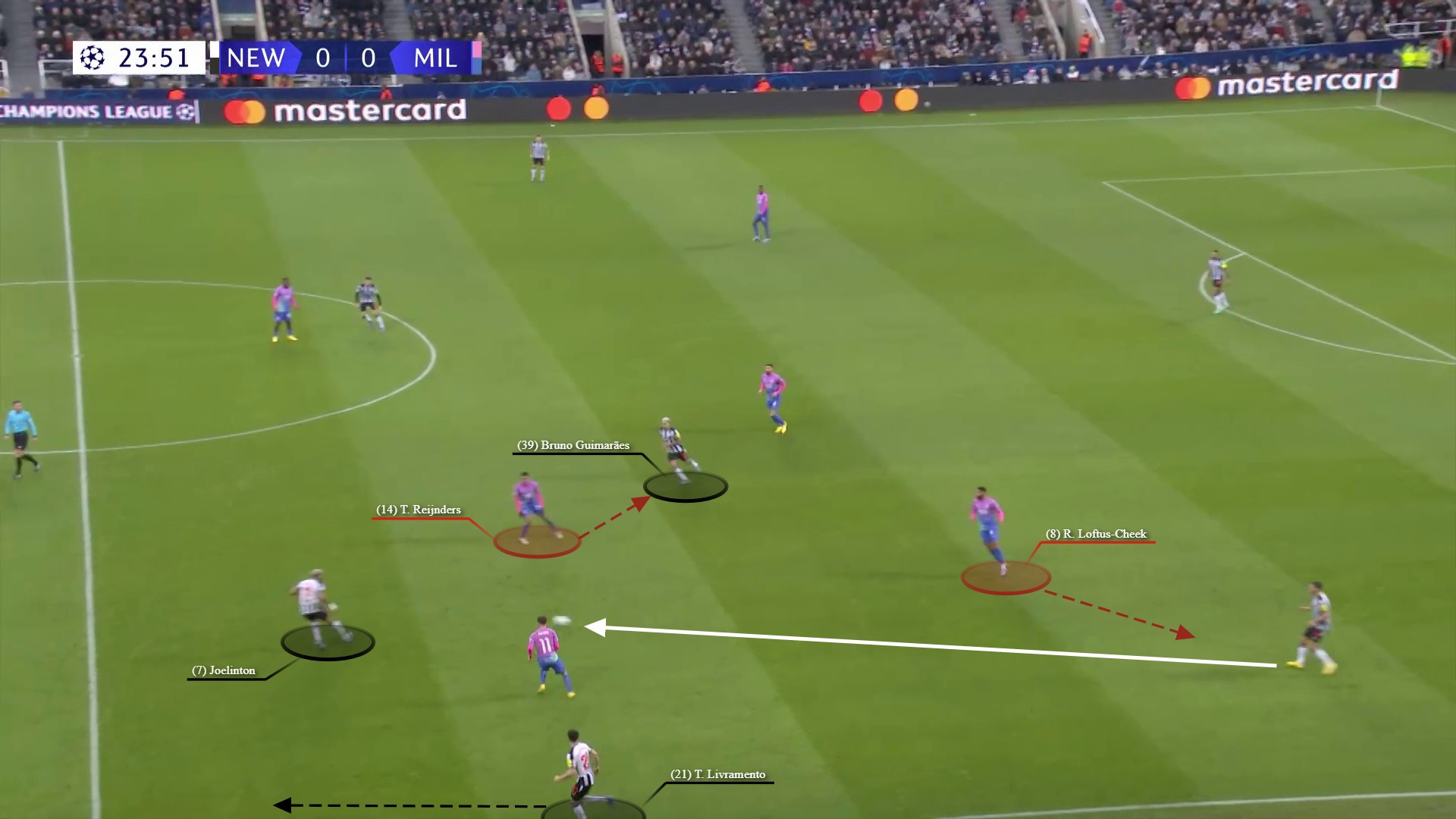

Shortly before the twenty-minute-mark, Newcastle showcased another tactic to exploit their man advantage in their backline, plus, how they freed one of their central midfielders. The passage of play started with a deep freekick that Guimarães dropped to take, which gave Loftus-Cheek a decision to make.

Once the ball was passed short to Schär, the defender began to pull wider with the ball which caused Loftus-Cheek to vacate Guimarães and engage. Loftus-Cheek was often Milan’s highest-positioned midfielder, so it was his responsibility to jump and engage any central defender progressive carry (most typically Schär), if Giroud was not able. The French striker, the central player in the Milan forward line, was responsible for splitting the two Newcastle centre-backs and angling his engagement, preventing access to the other with his cover shadow.

However, in this passage, he was not in the optimal position too, so Loftus-Cheek needed to engage. Schär played wide to Livramento who then passed forward to the dropping Gordon who helped complete the third-man combination to access the now free Bruno Guimarães.

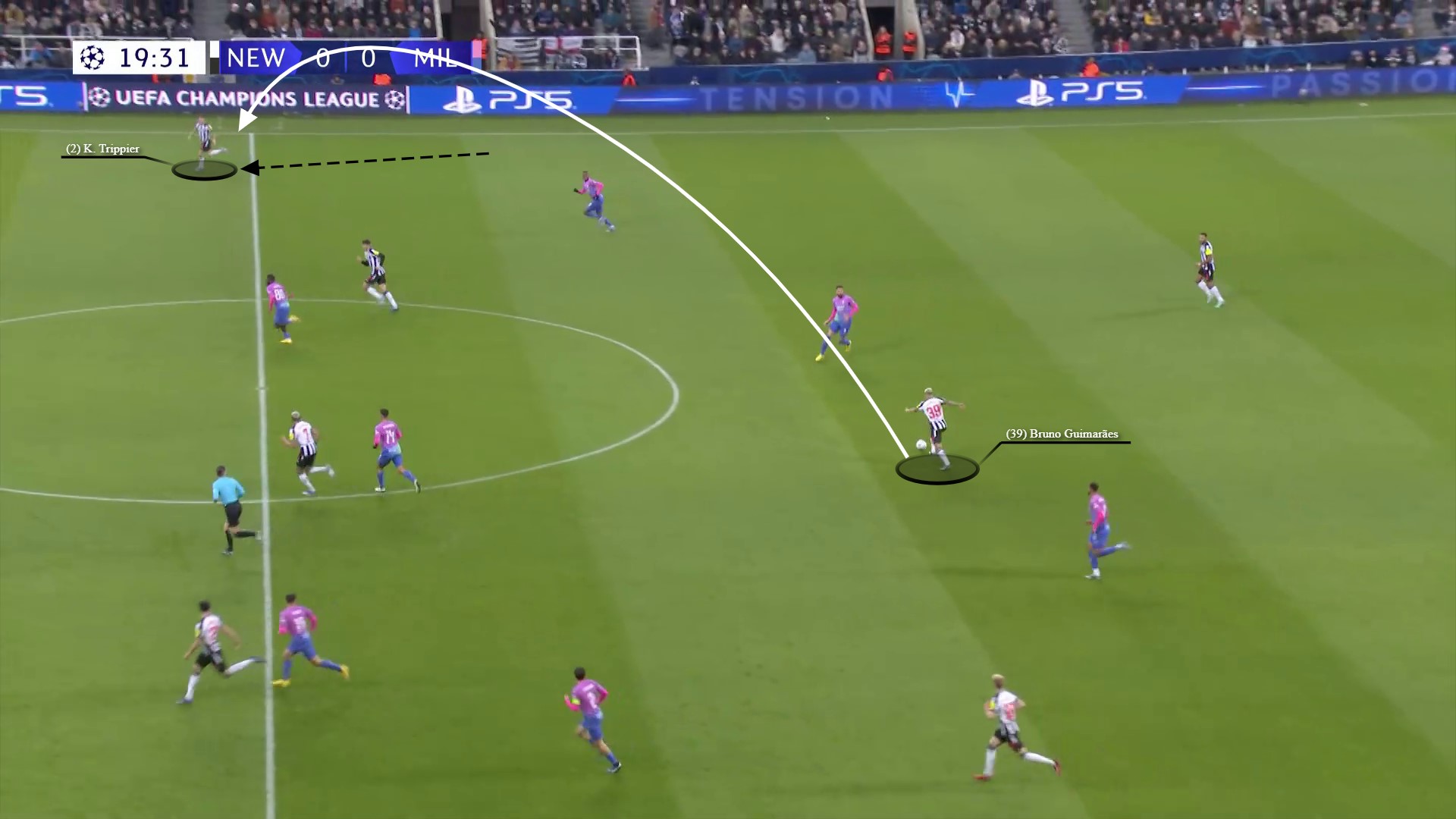

From here, Guimarães, with time and space in central midfield, played a diagonal switch to the right wing, where – yes, you know the drill – Trippier had advanced on the blindside of Leão to receive.

As Almirón had again pushed infield to pin Florenzi, Trippier was able to carry towards the final third. Lewis Miley made an off-ball run in behind to attack the space Florenzi had vacated, but Trippier instead played a through ball to Joelinton who had made a crossfield diagonal run, before attacking the box.

Joelinton thought he was squaring for Almirón to tap-in, but Fikayo Tomori had other ideas with a heroic last-ditch tackle-come-block to deny Newcastle from taking the lead.

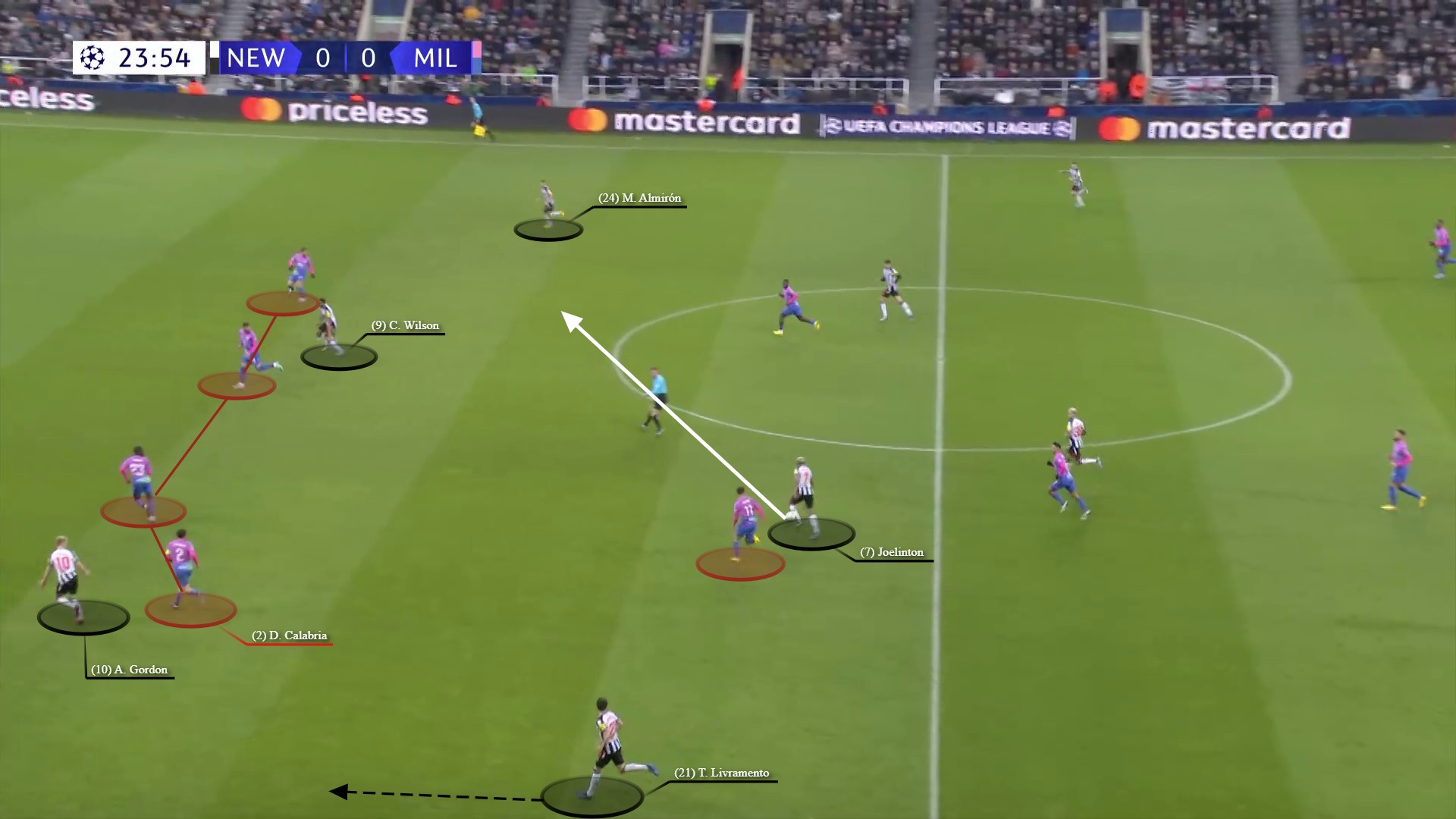

Late in the 24th minute, Newcastle easily played out from a goal kick to access a free Schär. With potential space ahead to progress into, Loftus-Cheek – initially performing his first defensive priority, covering the deepest Newcastle midfielder – was triggered into performing his secondary role, vacating his player to jump and engage the free centre-back.

Whether this was a newly devised solution or always the plan, and it just didn’t occur in the first instance, once Loftus-Cheek jumped vacating Guimarães, the near-side central midfielder (Reijnders here) left his midfield opponent to cover the now free Guimarães.

However, this had a knock-on effect, as Reijnders was required to vacate his initial marker in the process – which, as you can see below, left Joelinton free to receive a line-breaking pass from Schär.

What the static screenshots cannot show, is that in this action Calabria was visibly indecisive as whether to jump and cover Joelinton or stay attached to his backline, especially with Gordon strategically positioned in between himself and Tomori. Calabria stayed put – perhaps wary of how much distance he had to make-up – allowing Joelinton to receive between the lines with time and space ahead to make his next move.

Milan were spared punishment in this possession, with Joelinton’s attempted pass to Almirón intercepted. However, a turnover soon occurred and Newcastle regained the ball.

Both teams quickly settled back into their respective offensive and defensive default structures, and then Schär reverted back the playbook to execute a diagonal switch to the right flank where Almirón was inverting to manufacture space for Trippier to advance into.

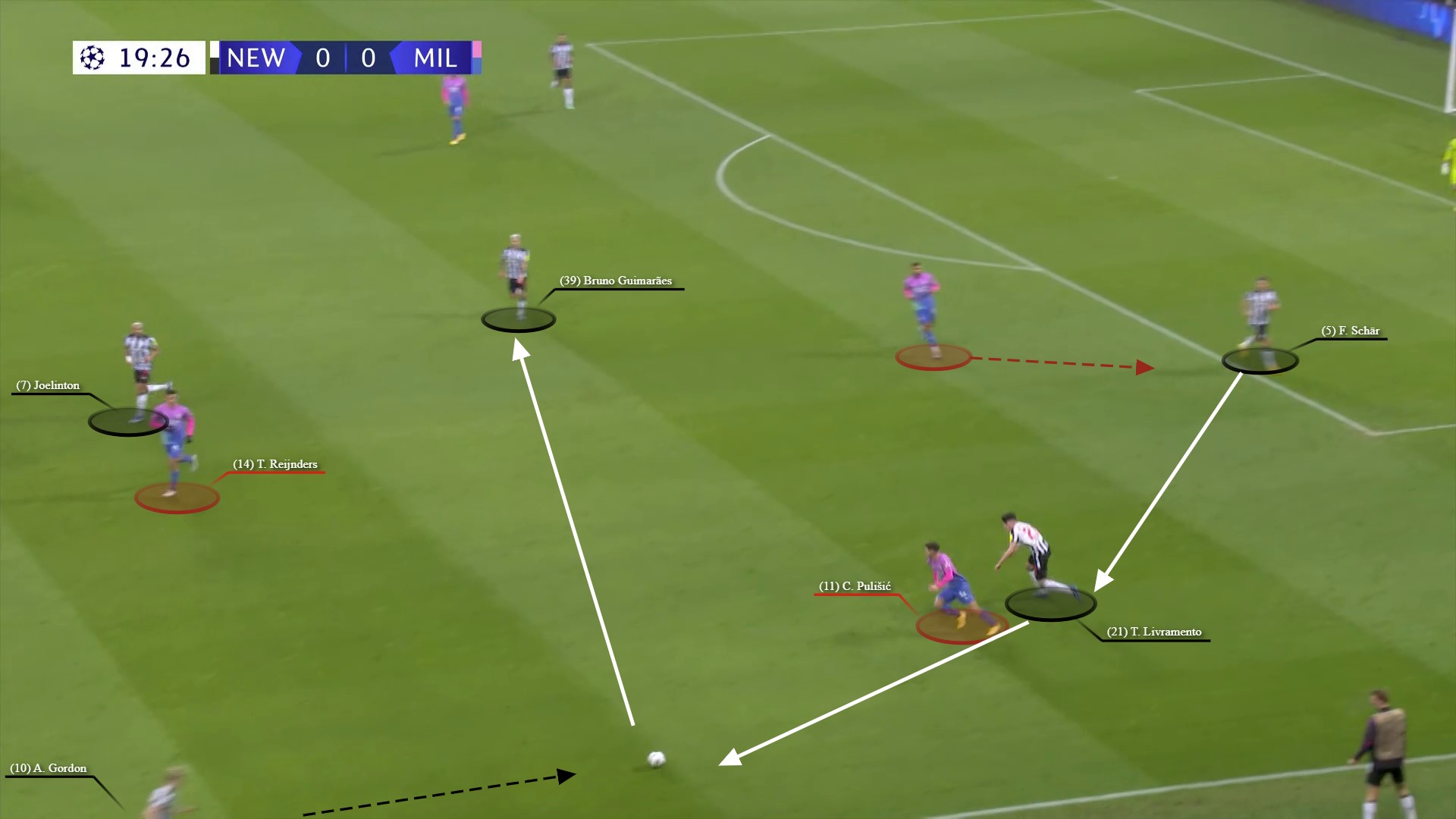

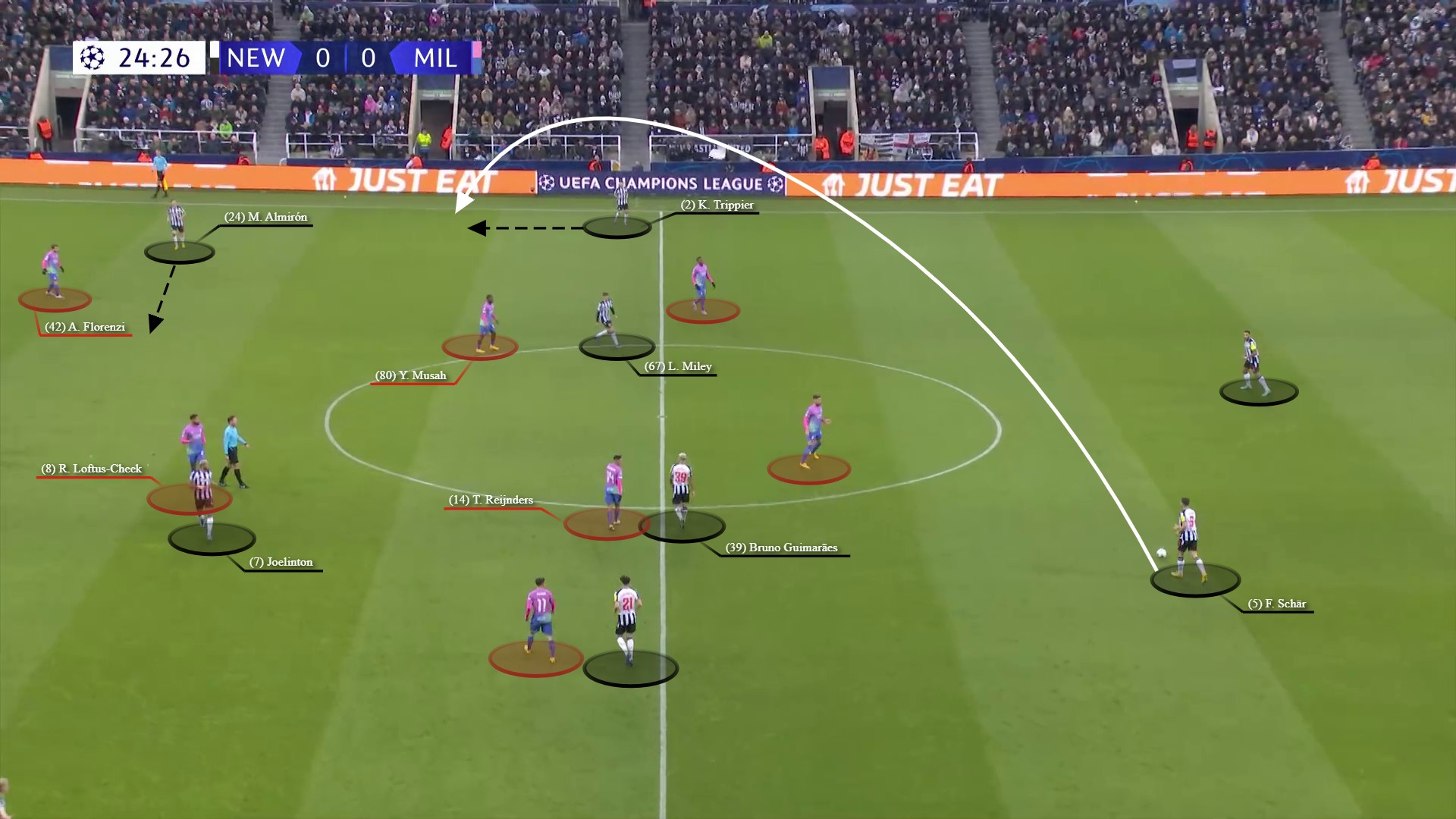

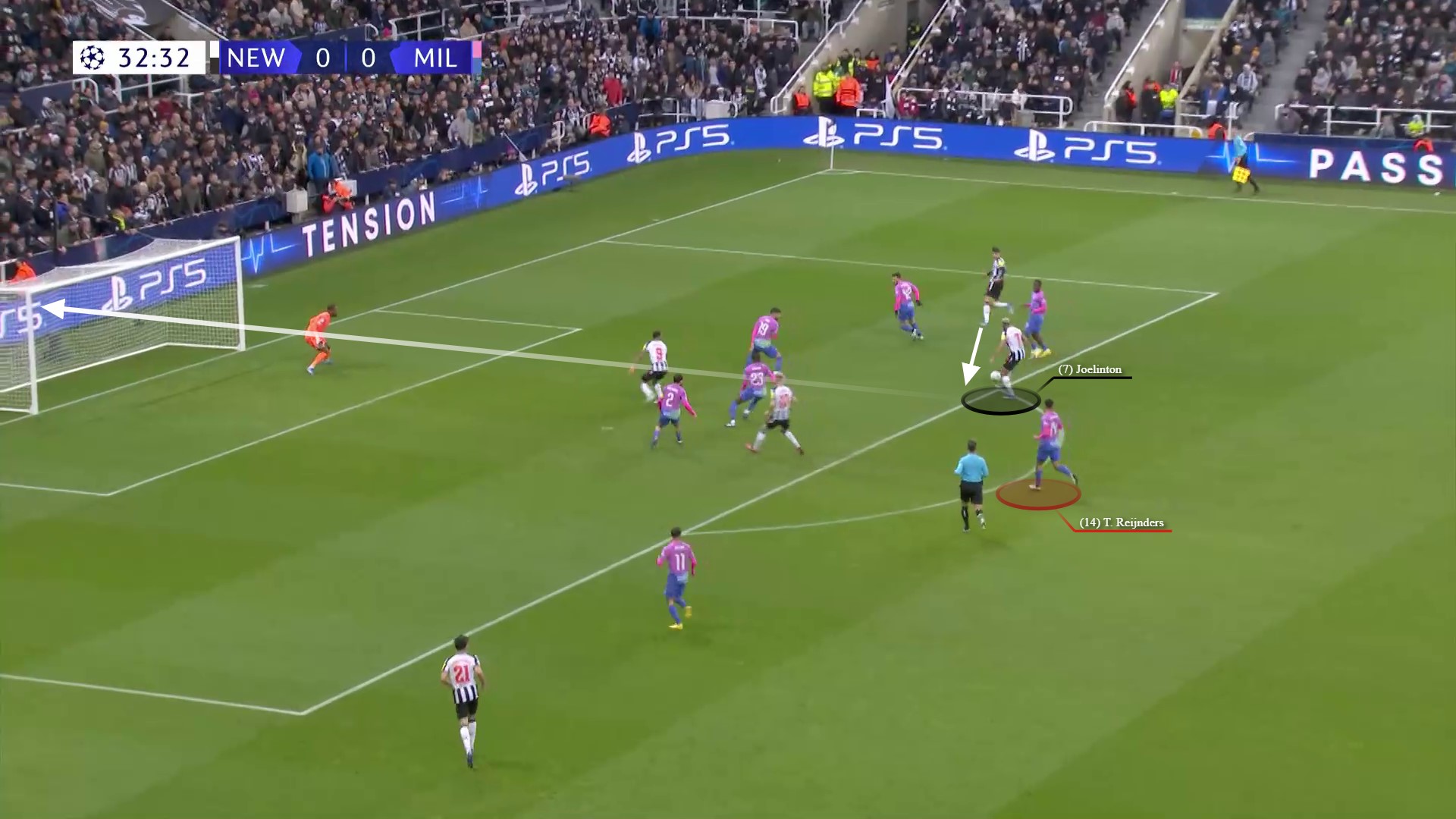

Newcastle’s attacking principles and specific tactics also played a role in their goal. The build-up initiated with a Milan turnover in the final third. With each team respectively transitioning from attack to defence and vice versa, Guimarães easily found Schär with space ahead to carry.

In the visual below, you can see Milan’s midfielders are all player-oriented, and as a result of this action shortly following a transitional moment, Loftus-Cheek was not the most advanced Milan midfielder. Therefore, he was unable to immediately engage.

Another issue for Milan was Gordon inverting into the pocket of space between the lines to receive the line-breaking pass. Again, the screenshots do not serve justice to the coordinated timing of Gordon’s movement inside and Livramento’s overlapping run, forcing Calabria into another split-second ‘pick your poison’ dilemma.

Whilst Gordon and Livramento were making their off-ball movements, Loftus-Cheek was jumping to engage the progressing Schär, vacating Joelinton in the process. Granted Loftus-Cheek was ‘performing’ one aspect of his defensive role, but when considering the reference points that help inform players decision-making e.g. ball, opponent, teammate, space, the English midfielder made a consequential action.

With midfield teammates ahead of him, so unable to cover in behind, his forward engagement left Joelinton free – with neither centre-back seemingly willing to jump and cover either (an ongoing theme from the first half).

The outcome, the free Gordon passed onto the free Joelinton who passed out wide to Miley whose cutback found Joelinton to half-volley into the top corner with no Milan midfielder recovering in time to pick up.

In a number of the provided examples above, including the goal, one solution to Milan’s issues could have been to jump a defender from their backline more proactively, lowering the risk of the midfield unit leaving opponents unmarked behind. And frankly, this is a tactic Milan usually perform in their most typical out-of-possession approach. Perhaps, Milan didn’t want to risk leaving their backline exposed (a trade-off of a defender jumping out is that it can leave 1v1s elsewhere).

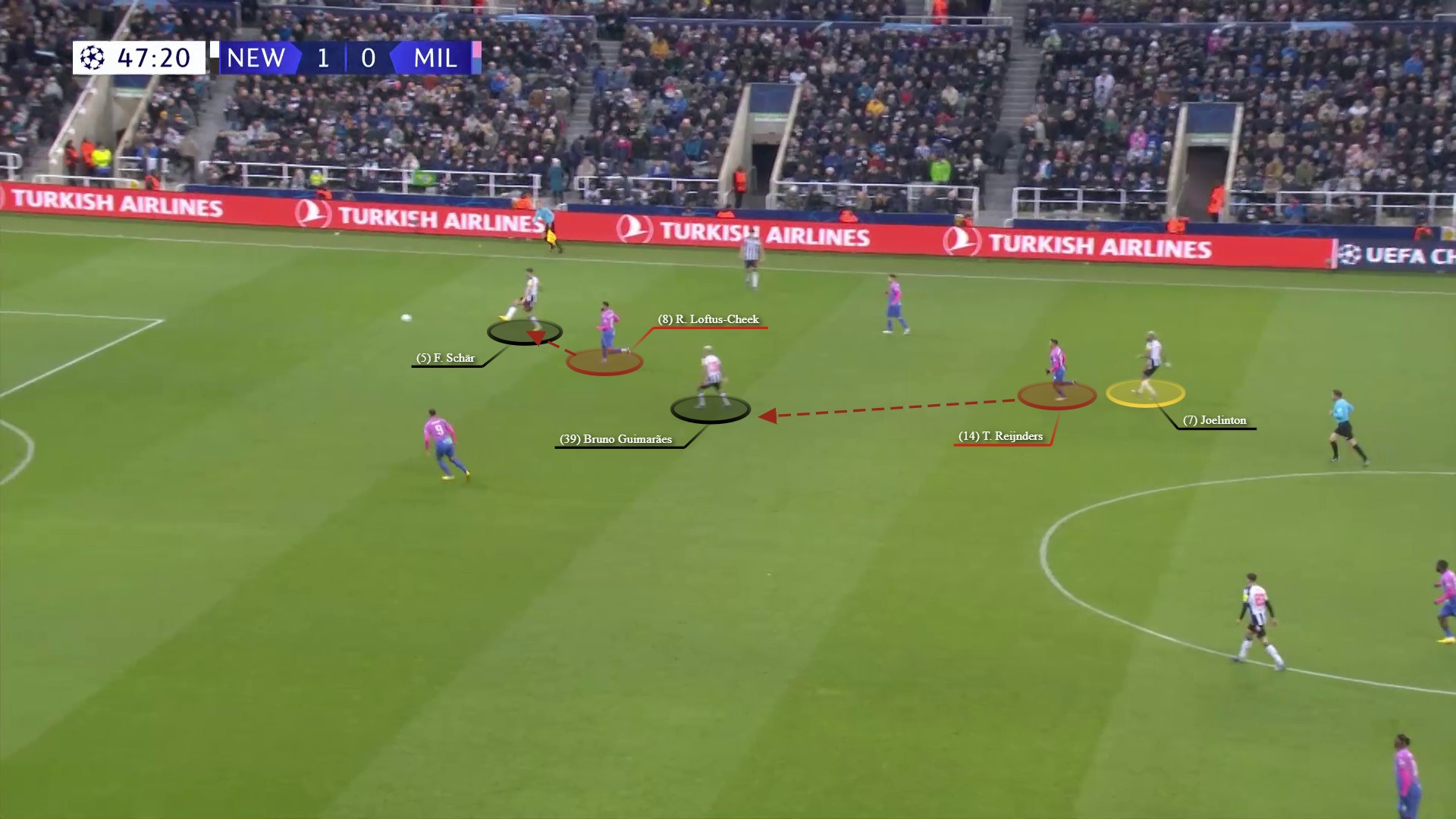

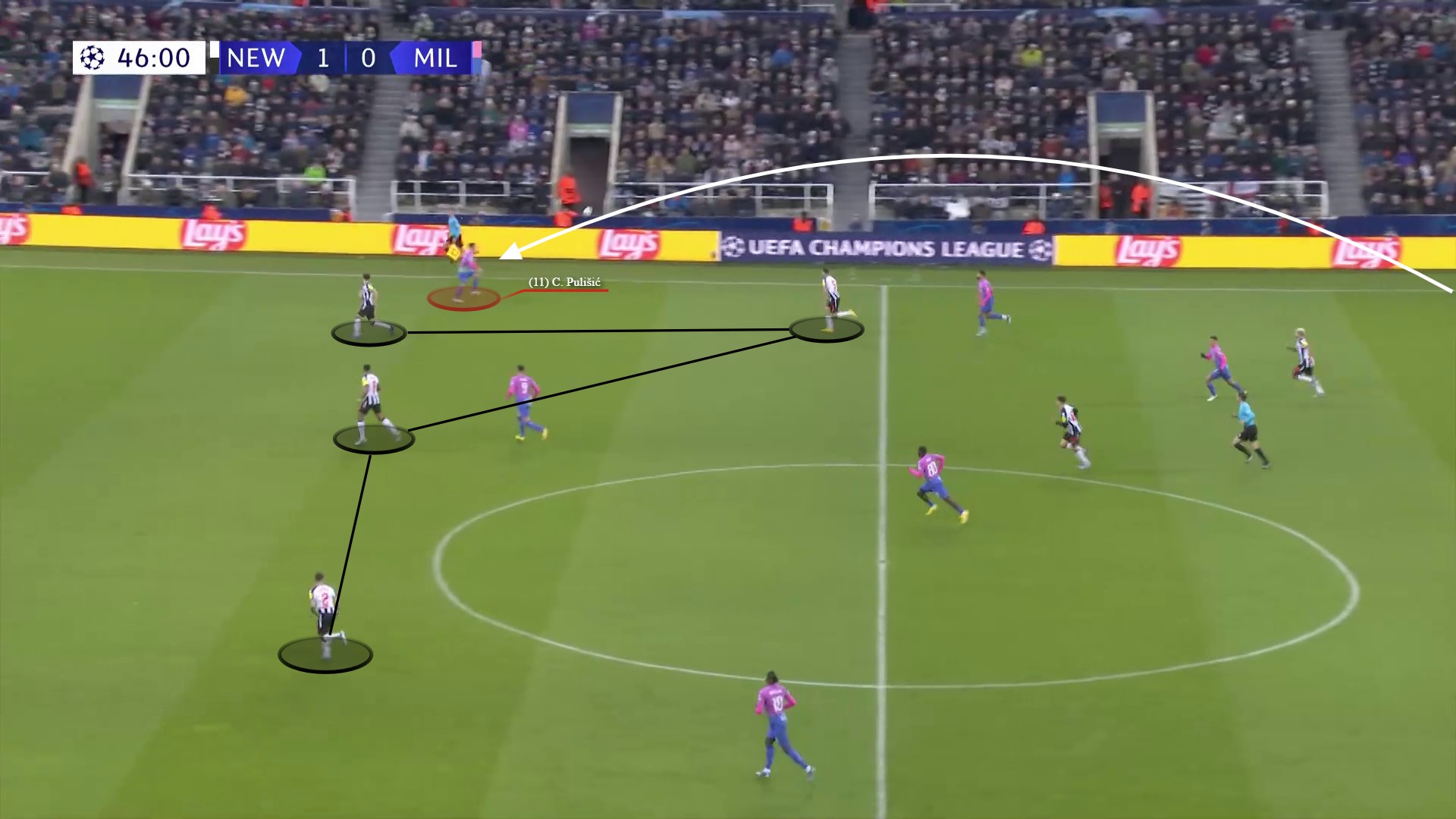

But with new problems occurring from this slightly tweaked approach, in the second half, Milan reverted back to what they knew best. So now, when Loftus-Cheek jumped, Reijnders covered him and when the Dutch midfielder jumped, Tomori now pushed out of the backline to cover him.

But this was not the only needed change in approach Milan needed after the break. As in possession issues were equally a factor in the current result and underwhelming performance.

Second-half retention

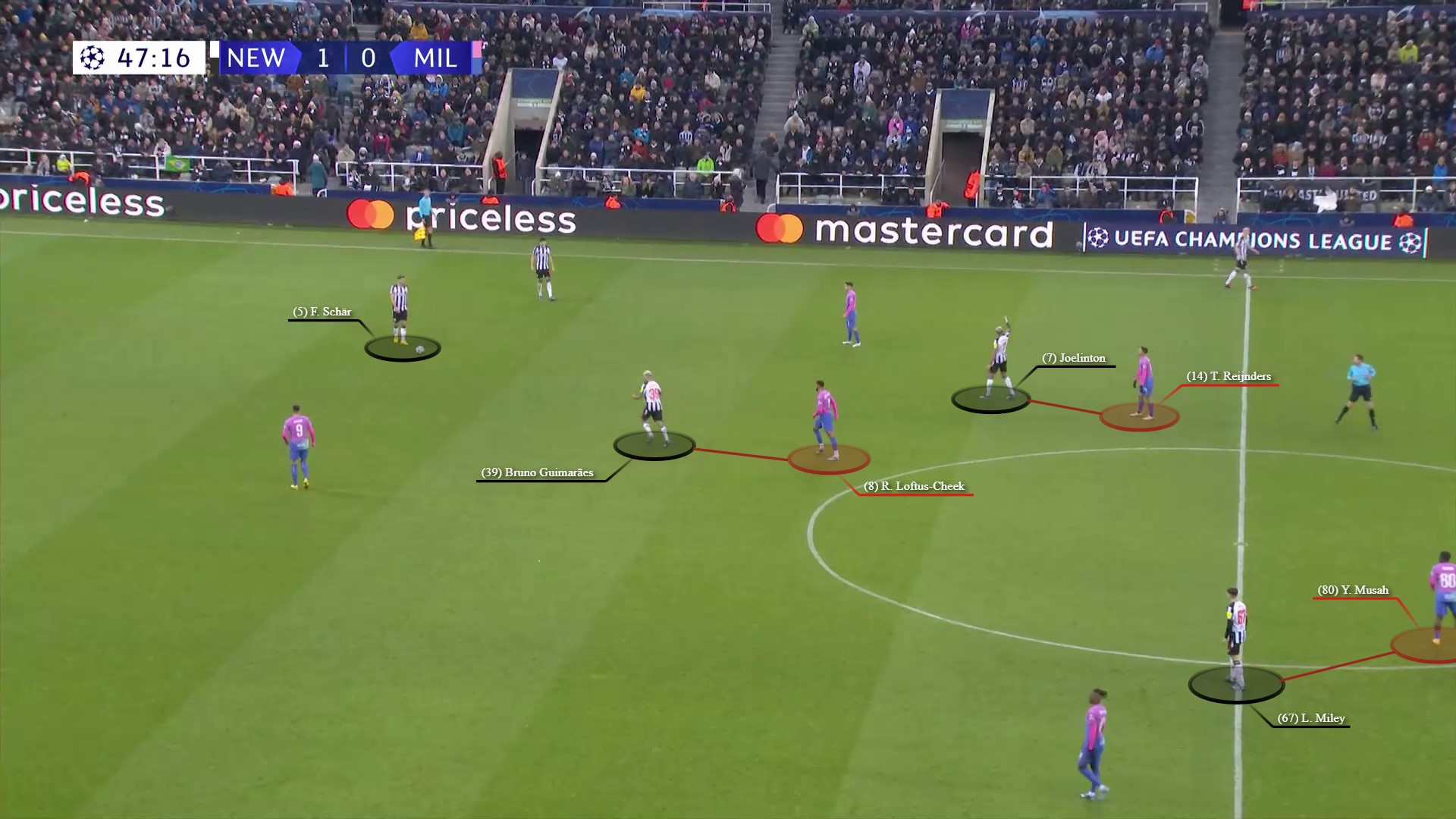

For a tactically focused match analysis, attributing Milan’s second-half turnaround to keeping the ball better may seem too simplistic, but it certainly played a factor. In the opening fifteen minutes after the restart, Milan had 65% possession – a significant shift compared to the first half.

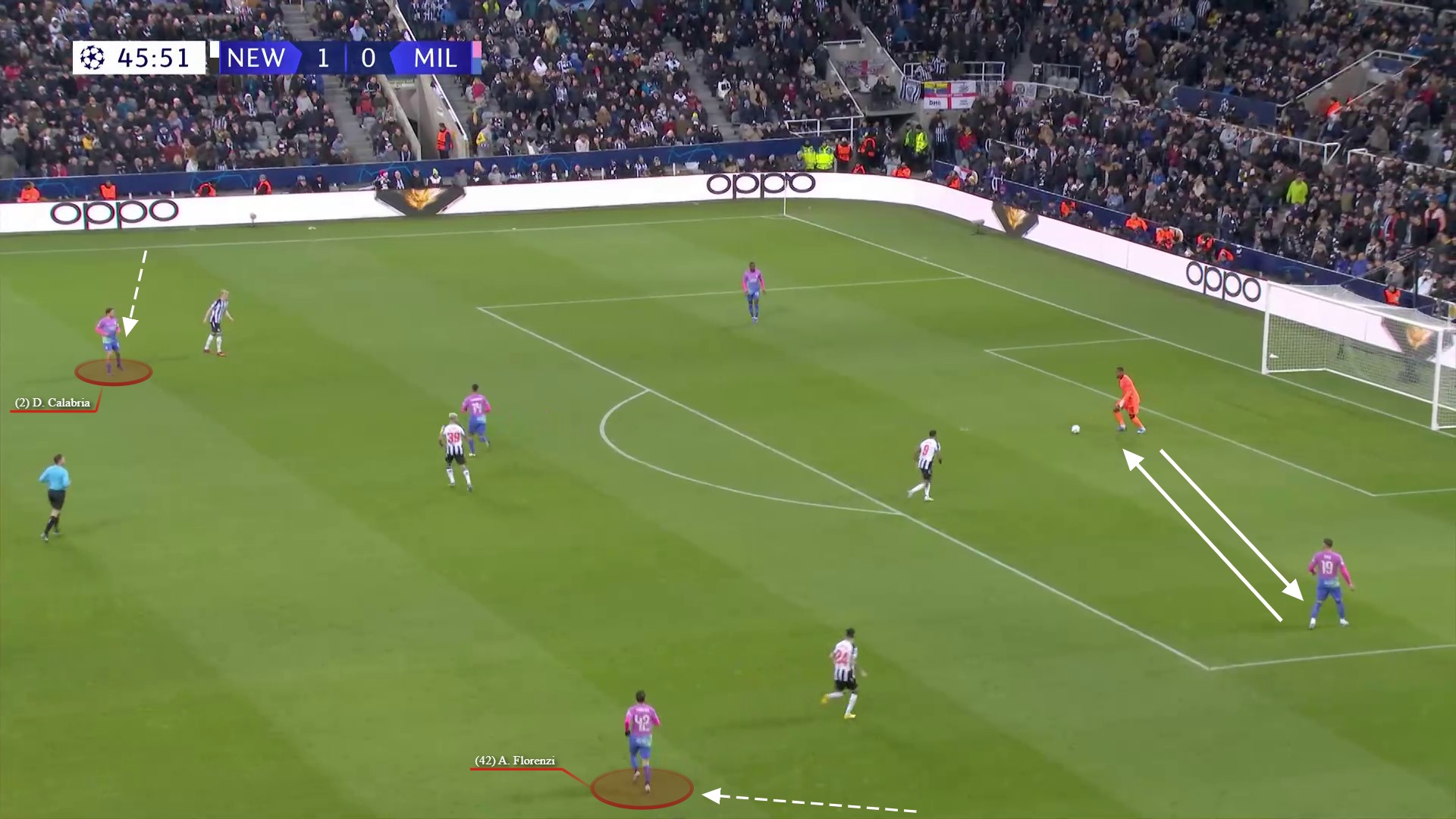

Milan’s change in intent was visible from the 46th minute. This was Milan’s first settled possession sequence after the break and it started with a short goal kick and exchange of passes inside their own penalty area to bait the press.

Milan’s full-backs both continued to push infield to not only narrow the Newcastle midfield line, but also…

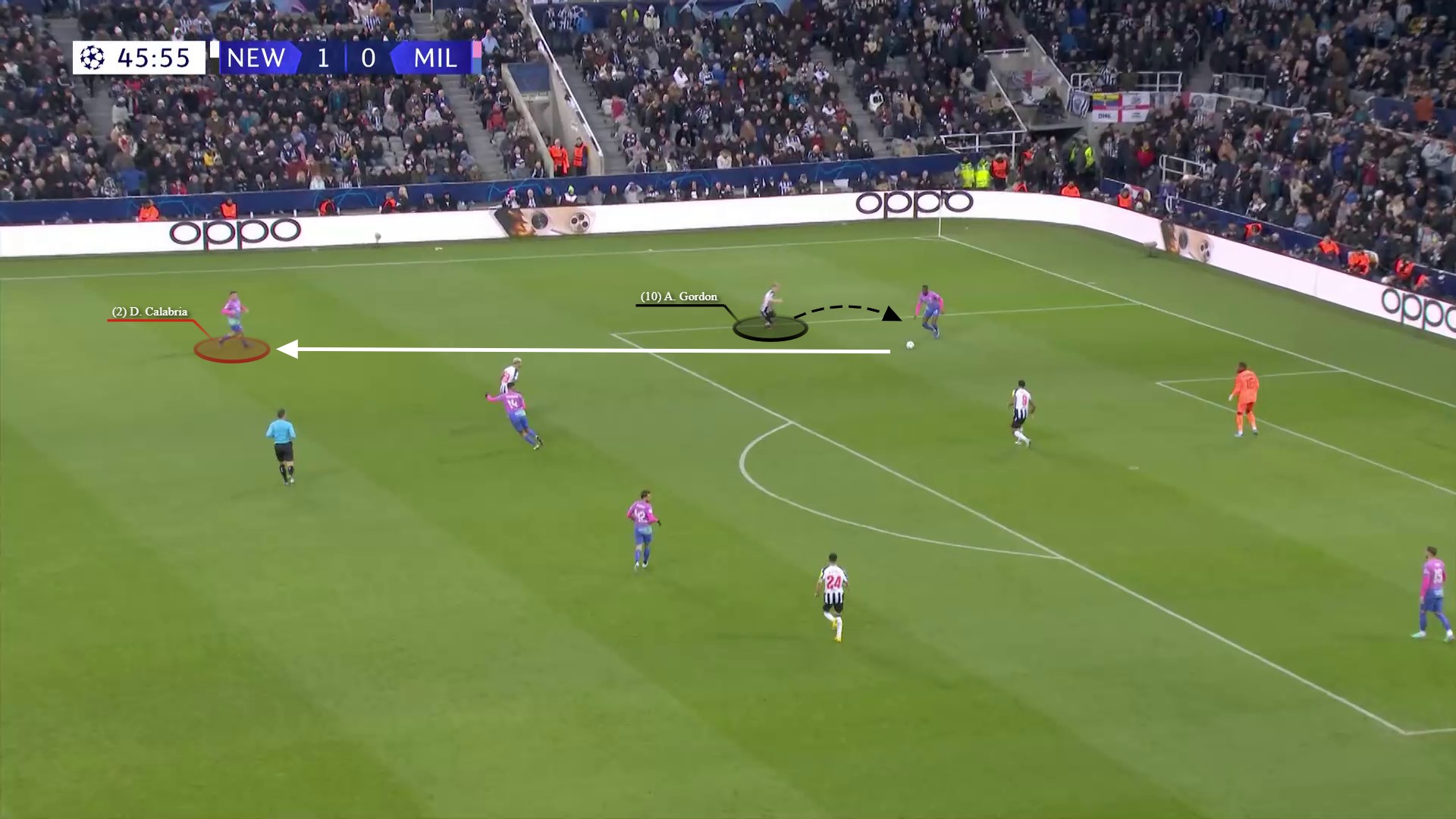

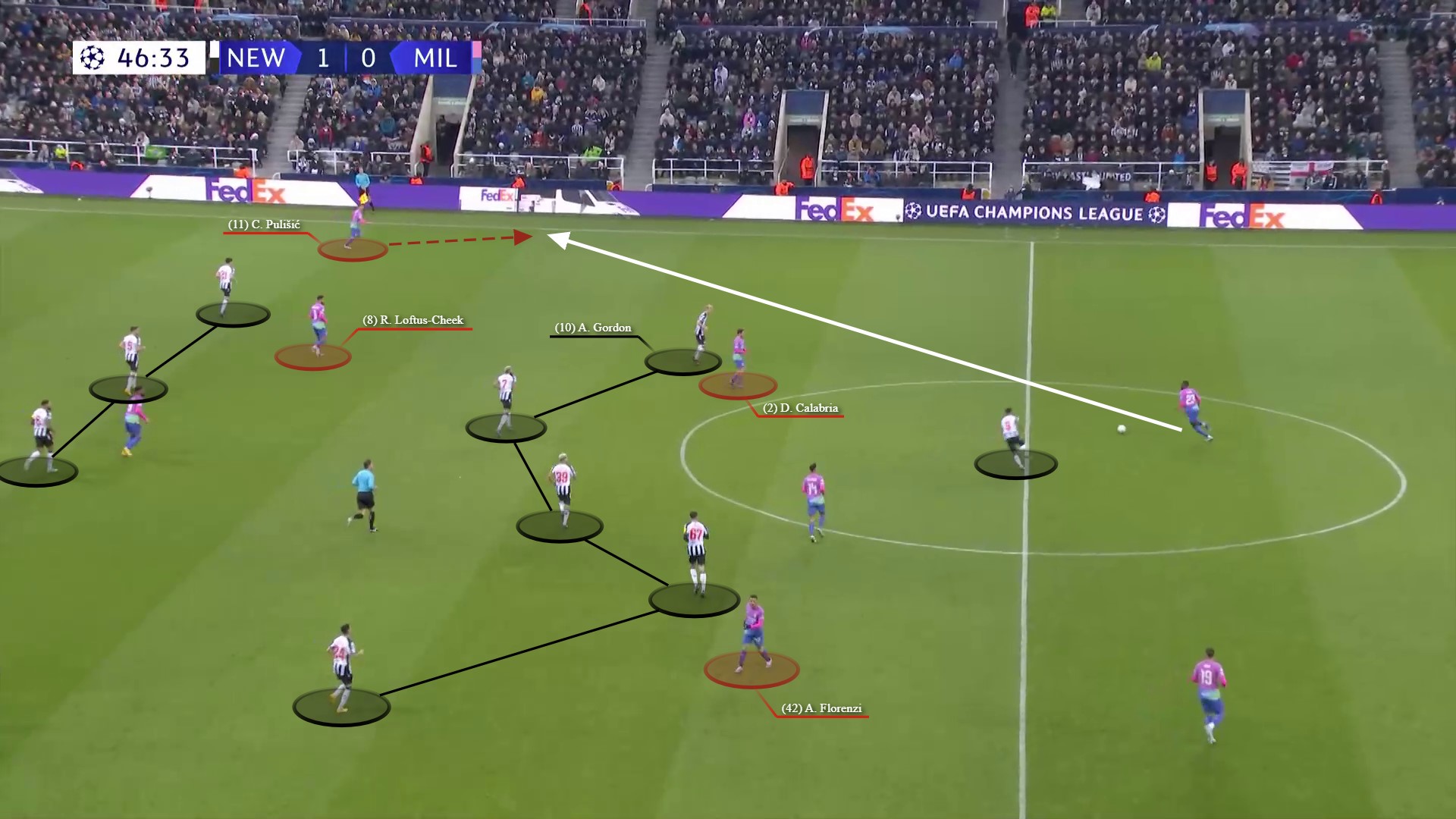

…receive in behind when the Newcastle wingers made their out-to-in pressing movements forward. Below, is a perfect illustration of Milan’s new composed build-up approach, with Tomori side-stepping before breaking Newcastle’s first line of pressure with a pass into Calabria.

Calabria, after assessing the Newcastle backline had become disjointed with a centre-back jumping out to pick up Loftus-Cheek, clipped a pass forward for Milan to progress into the opposition half.

But Milan’s new intent to focus on patient ball retention was again demonstrated with a recycle of possession. After both teams got into their respective settled structures, Tomori was able to find a pass out wide to Pulisic, aided by the Milan full-backs infield positioning to narrow the Newcastle wingers position. The USMNT international then passed into the final to meet Loftus-Cheek’s channel run but the attack ended with a tame cross into the box.

This new possession-focused approach continued. And whilst the home team’s press still proved effective on occasions, the Serie A side’s perseverance in trying to play through contributed to increased ball retention and subsequently more control in the game. With a lead to protect, Newcastle started to prioritise maintaining their shape, further adding to Milan time on the ball.

This momentum shift also helped Milan gain territory in the Newcastle half, where their players’ growing confidence began to reveal itself. A perfect example of this was Reijnders dribbling past two opponents to win the corner kick which led to Milan’s equalizer.

At 1-1, the match became an end-to-end encounter, but with a win the only result beneficial for Milan, they had the advantage in this new game of Russian roulette.

In the end, Newcastle’s ever-increasing openness in search of a winner left them vulnerable on one too many occasions. With less than ten minutes to go, substitutes Noah Okafor and Samuel Chukwueze combined, within their first minutes on the pitch, to snatch victory and a ticket to the second tier of European club competition.

Up Next

Post-match, Pioli conceded that it was: “…a bittersweet evening.”

“Satisfaction with the victory certainly, but there is a bit of regret and disappointment at having exited the Champions League.”

With European football now parked until mid-February, focus fully switches to domestic matters. Next up, Monza at San Siro this Sunday. The taste of sweet victory in Serie A is much needed, with only two wins in their last seven. A defeat, however, and the clamour from sections of the fanbase for a bitter ending with Pioli will only intensify.